We recommend inviting a Knowledge Keeper or community member into the learning environment to help students understand the spirited epistemology of local Indigenous groups.

Instructions:

- The teacher begins by reviewing the vocabulary words biotic and abiotic with students. Students come up with a class definition for each. Teachers can discuss with students the ways in which biotic and abiotic components of an ecosystem interact and support one another.

- The teacher takes students outside to observe and sketch all the living [(biotic) eg: animals, plants, insects] and non-living [(abiotic) eg: rocks, water, waste] elements in an ecosystem. Students should also label each sketch as either abiotic or biotic.

- Ideally there will be a great diversity of biotic and abiotic elements in the ecosystem they visit.

- If so, students can review all the benefits of biodiversity to an ecosystem.

- If not, students can discuss if the ecosystem has always looked this way or if it was altered. Students can also discuss if these changes are inevitable and permanent or if there is a way to restore some of the biotic and abiotic elements that have disappeared.

- Next, teachers give students the opportunity to free-write about all the connections they observe in the ecosystem. Ie: the interactions between the biotic elements and between the biotic and abiotic elements. The teacher leads a discussion with students about how Western scientists see an ecosystem as a network of interactions among living and non-living organisms and their environment.

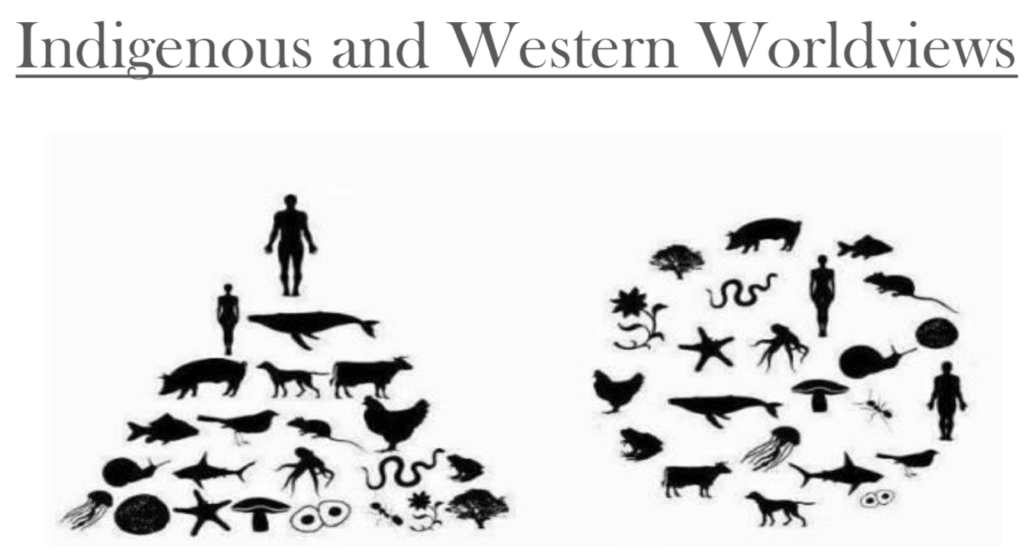

- Teacher then explains that many Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee folks that inhabit this local territory do not divide elements in the ecosystem into biotic (living) and abiotic (non-living). Instead, they understand that all elements in the natural world are ‘spirited’ as they are imbued with a spirit from the Creator.

- In this sense all elements of an ecosystem are equally valuable eg. There is not a hierarchy in which biotic elements are seen as more valuable than abiotic elements. Additionally, all living things are valued equally. Humans and animals are not positioned as being superior to plants and insects etc.

Image taken from commoxvalleyschools.ca

- It is important to reflect with students on how there are many Western scientists who, like Indigenous community members, are beginning to see the interconnections between all living and non-living things (even though the above imagery clarifies fundamental differences between Indigenous land-based knowledge (IK) and the Western capitalist worldview). For instance, since evolution has come to be understood more clearly by scientists it is believed that things evolved in a web from the first organism. In this sense all living things are related and one is not necessarily understood to be superior to another. The discipline of Community Ecology within the Western Scientific paradigm demonstrates this understanding.

- Community Ecologists study the interactions and relationships that exist within a particular community, as well as the interplay of factors that affect biodiversity, community structure, the abundance of species, and the overall dynamics of a particular species. The core values underpinning this field involve:

- the awareness of relationship between species and environment

- the overall web of interconnectedness that lies within a community, to which these understandings could inform conservation practices, resource and ecosystem management, community health, and human development.

- In this manner, the way in which community ecologists see the interconnectedness of all elements in an ecosystem is similar to Indigenous land-based knowledge (ILBK). This is a good reminder that there is not a dichotomy between the two worldviews but instead many ways in which they are complimentary and overlap.

- One way, however, in which Indigenous worldview and ways of relating to the natural world are distinct from Western science is that they are holistic or spirited. This can be understood more clearly by examining the relationship the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe locally have to both abiotic and biotic elements.

Abiotic Elements:

Water:

Spotlight on Language:

- Anishinaabemowin – Nibi

- Kanien’kéha – Ohneka’shon:a

Note that students can go onto the online QUILLS dictionary to hear these word.

The way the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe view water is an example of how local Indigenous groups view BOTH biotic and abiotic things as spirited. To learn more about this the class can examine the following quotation from respected Haudenosaunee Elder Tom Porter:

“Water is not just water, it is sacred. Every water is sacred. Every water is holy everywhere in the whole world. The water has spirit, it has a soul, it has life in it. The Creator said to the water, ‘And your job, Water, is to move, to look for the humans, look for the birds, look for the bears, look for the deer.’ That is why the water is moving. It’s doing its job, going looking around for the life. And then it goes into the big river and then into the big ocean and then back into the clouds. Around and around refreshing because it is alive. It is refreshing because it gives life. That is what the waters do, they quench our thirst, and they clean and purify our body so that we may have a healthy, good life. Then when you listen to the oceans and the big lakes, you hear the heartbeat of the water. You see that it is living. The big waves come, and they hit Mother Earth. It is the same thing as what is going on right in your heart. It is beating with a rhythm because it is living.” Tom Porter- And Grandma Said

- Teacher asks students to discuss how this quotation reflects the holistic relationship Indigenous groups have with water.

- To learn more about the local Indigenous relationship to water the class can engage in Learning Activity 3: Relationship to Water in the Water Bundle.

Rocks:

Spotlight on Language:

- Anishinaabemowin: Asiniin

- Kanyen’ké:ha: Onèn:ya

Note that students can go onto the online QUILLS dictionary to hear these word.

- The relationship local Indigenous groups have with rocks demonstrates another example of the holistic relationship Indigenous groups have with both biotic and abiotic elements.

- For instance, Ojibway and Métis Knowledge Keeper Deb St. Amant shared with QUILLS that the Anishinaabe view rocks as their grandfathers (Mishoomis) and grandmothers (Nokomis). The Anishinaabe believe that rocks contain the spirits of ancestors and are animate being with memories and stories to share.

- The Haudenosaunee also view rocks as spirited. This understanding is expressed in the Grinding Stone Resource shared with QUILLS by Kahehtok:tha educator Janice Brant who sits with the Bear Clan in the Kanyen’kehá:ka Mohawk Nation of the Rotinonhsyon:ni Six Nations. This resource was explored more deeply in this Learning Bundle Learning Activity Five: Food Production-The Grinding Stone.

- Teacher shares the following excerpt from the resource with students:

“Indigenous cultures have a sacred and spiritual ecology or relationship with nature. We understand that all living beings have a spirit, and we acknowledge that the stones have had a journey and a long life. They have seen many generations of human hands over such a long time. We communicate our respect by calling them Grandmothers. This is a term of kingship, endearment, and affection. When we are preparing to use the grinding stones, we offer tobacco and express our greetings and intentions. We also smudge the stones with sacred cleansing medicines. We give gratitude and thanksgiving for our ancestors that used and created this tool, we give thanks to the spirit of these Grandmothers, and we thank them for continuing to teach us and share their ancient wisdom.”

- Teacher asks students what they think this passage reveals about the Indigenous relationship to the tools they rely on and the materials from the natural world that they are made from.